Navigating Manufacturing Challenges

By Dan Deisz, Rochester Electronics’ Vice President, Design Technology

There are many factors in any semiconductor product “puzzle” that can lead to obsolescence. These pieces range from business revenue to subcomponents of semiconductor products, including foundry process technologies, packages, substrates, lead frames, test platforms, and design resources. The puzzle pieces often include any given semiconductor company’s overall corporate or market focus. Market foci may change over time for a semiconductor company, even while a long-term system company, such as a customer, may not alter its product focus. Given the long-term availability risks inherent in any product selection, the part numbers offered by original component manufacturers extend well beyond the bill of materials (BOM) health reports provided by commercially available tools.

How does the manufacturing supply chain impact long-term product availability?

Most older semiconductor products are assembled in leadframe packages, such as DIP, PLCC, QFP, and PGA. However, the semiconductor market has shifted from leadframe packages as the primary volume driver to substrate-based assemblies.

Why did the industry move away from lead frame assemblies?

To fully understand why lead frame assemblies are disappearing, it is important to address the history of assembly locations, profit margins, and the move toward ever-increasing performance.

Assembly offshoring started happening in earnest during the 1980s. This was before TSMC’s dominance in foundry technologies. Costs and environmental restrictions primarily drove offshore assembly, as 1980s assembly processes were less environmentally clean than those of today. The push for higher profit margins gradually eliminated numerous leadframe suppliers from the market, leaving only the largest suppliers profitable. Profit margins on lead frames were reduced to single digits, whereas most semiconductor companies’ margins trended toward 50%. Lead frame volumes peaked in the 1990s and early 2000s, concurrent with the push toward high-speed IO and the invention of BGA assembly. High-speed I/O protocols, such as PCI Express, multi-gigabit Ethernet, SATA, SAS, sRIO, and others, have demonstrated that wire bonds limit performance. The IO standards and other new standards coming online had performance roadmaps that wire bonds would never have met. As device speeds increased significantly, so did their power.

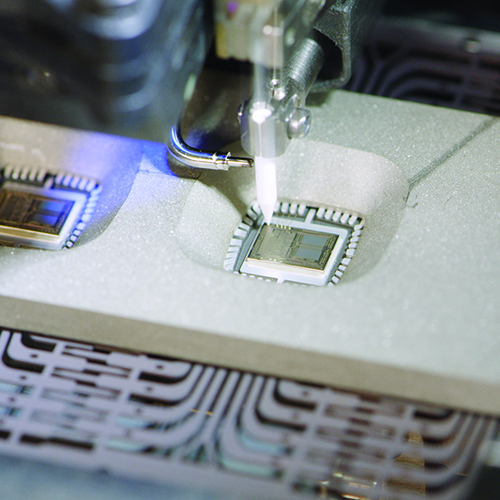

A wire bond distributes power from the chip’s exterior to the core. For higher-performance products becoming available in the 1990s, supplying power to the device from outside the die was insufficient. Flip-chip and BGAs with substrates alleviated the power distribution challenge by delivering power directly to the core and eliminating bond wires, thereby improving signal integrity for high-speed SerDes standards. As leadframe assemblies declined in the early 2000s, QFN assemblies emerged for lower-pin-count packages. QFNs are substrate-based assemblies that primarily use wire bonds in high-volume production. Today, leadframe assemblies are produced in far lower volumes than substrate-based assemblies. The highest cost of installing lead frame assemblies is the trim-and-form tooling. As the volume of lead frames has diminished, the cost of replacing leadframe trim and form tooling, coupled with the single-digit profit margins of offshore suppliers, has put enormous pressure to move away from lead frame assemblies altogether.

The industry moved away from lead frame assemblies because technology performance demanded zero wire bonds, and the costs of continuing to produce lower-volume lead frame assemblies were prohibitive.

Once an assembly solution is in place, a test solution must also be viable. Consider the same trends in tester technology that enable the transition to substrate assembly testing, where disconnects may result in obsolescence. The newest handlers for production Test are primarily geared toward substrate-based assemblies. Efforts to reduce costs for volume production are currently based solely on substrate assemblies. Test for lower volume production at an OSAT location is less feasible as volumes diminish, especially if that product is lead frame-based.

Assuming wafer availability, what if a company acquired an existing OSAT supply chain to continue providing the same semiconductor product?

This is what Rochester Electronics believes is a short-term solution. Recall the manufacturing puzzle pieces we have examined, from lead frames and assembly to testing. If any link in the OSAT chain is deemed economically infeasible, an obsolescence event is expected. The risk of obsolescence increases because any company supporting the OSAT supply chain cannot drive product volume as the original semiconductor company would have. Therefore, that company cannot leverage the same level of product continuation. In the short term, OSAT chain management can keep a product in production, but it is not typically viable in the long term.

Partnering with a licensed semiconductor manufacturer, such as Rochester Electronics, can mitigate the risks of component EOL. A licensed manufacturer can produce devices no longer supplied by the OCM. When a component is discontinued, the remaining wafer and die, the assembly processes, and the original test IP, are transferred to the licensed manufacturer by the OCM. This means that previously discontinued components remain available, are newly manufactured, and fully comply with the original specifications. No additional qualifications are required, nor are any software changes.

Find out more: www.rocelec.com

Learn more about Rochester’s manufacturing service solutions

Watch to learn more about Rochester’s manufacturing capabilities

Sponsored Content by Rochester Electronics