Siemens has sponsored this post.

Seeing clearly is essential for education, employment and a general sense of wellbeing. In many parts of the world, getting eyeglasses that fit properly can be a luxury good. A simple pair of prescription glasses can cost weeks or even months worth of income. For children, that means learning becomes harder; for adults, work becomes less possible. A overlooked problem, left unsolved, becomes a generational barrier to success.

GoodVision (EinDollarBrille), a nonprofit organization headquartered in Germany, is working to change that equation through engineering, local empowerment and thoughtful design. Their mission is as straightforward as it is ambitious: make vision care accessible to people who would otherwise never receive it.

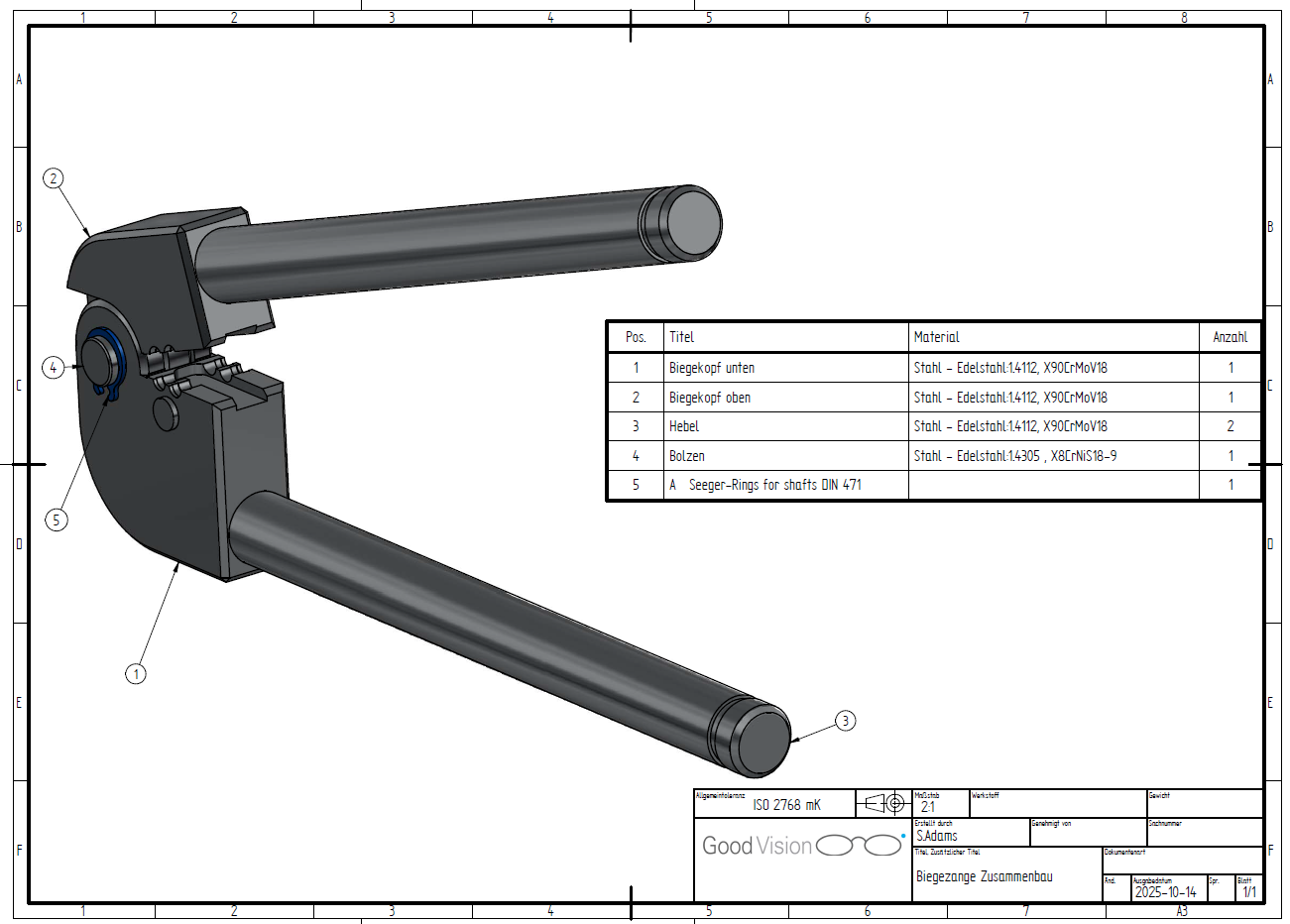

At the center of the initiative is a remarkably simple and durable pair of glasses. The frame is made from lightweight, flexible wire that is bent into shape using a portable mechanical forming machine. The lenses, which are generally the most expensive and technically precise component, are standardized in shape and “clicked” into the frames based on the user’s prescription.

Sabine Adams, Design Engineer at GoodVision, explains, “We go out with vans and people that do the testing and have the glasses with them. And so, we can go anywhere and do the testing and provide the glasses in one step.”

This simplicity is not an accident. It’s the result of iterative design rooted in a clear guiding principle: if the glasses are going to help the people who need them most, they must be buildable anywhere.

Simplicity by Design

The bending machine is the backbone of the GoodVision system. It requires no electricity, no specialized infrastructure and minimal training to operate. A single machine can travel in a small van to remote rural areas where medical resources and infrastructure are scarce. The team performs vision tests on-site, selects the correct lenses, bends the frame, and assembles the glasses — all in one visit.

That “one visit” concept matters. In regions where travel is time-consuming and expensive, asking someone to return later for their glasses is often unrealistic. GoodVision eliminates that gap by creating custom-fitting glasses in real-time.

The idea originated with a German schoolteacher, Martin Aufmuth, who noticed low-cost reading glasses in a dollar shop and wondered, “If a pair of glasses could cost so little here, why were they inaccessible to millions elsewhere?” With no background in industrial manufacturing, he began experimenting in his basement, shaping prototypes by hand, and seeking a way to make them repeatable and scalable.

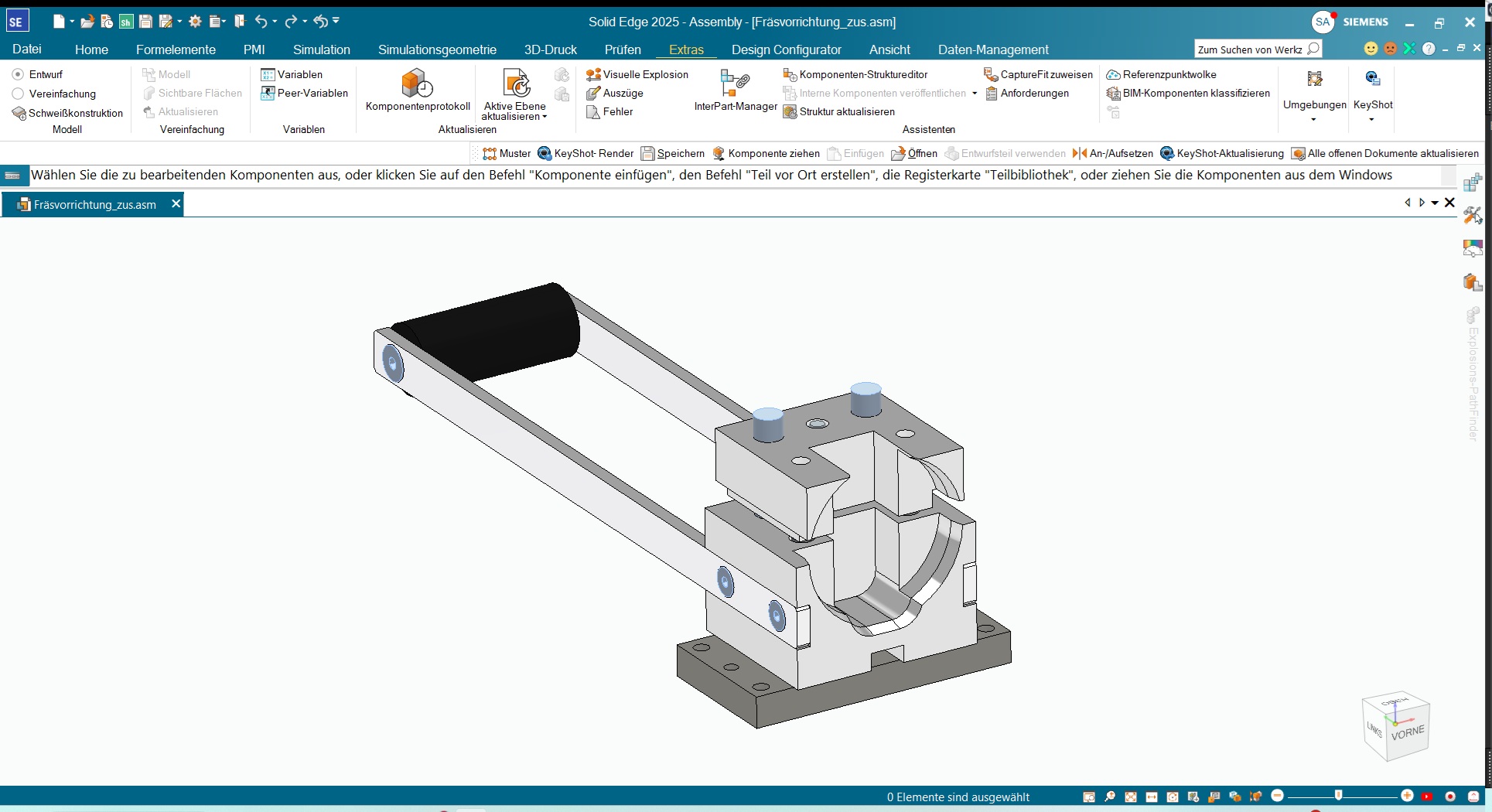

Designing a low-cost frame was only the first step. It needed to be manufacturable under a wide range of conditions, consistent enough to meet medical quality standards and durable enough for real-world wear. That led to the creation of the bending machine and eventually to multiple generations of improved models.

Simple Designs Still Need CAD

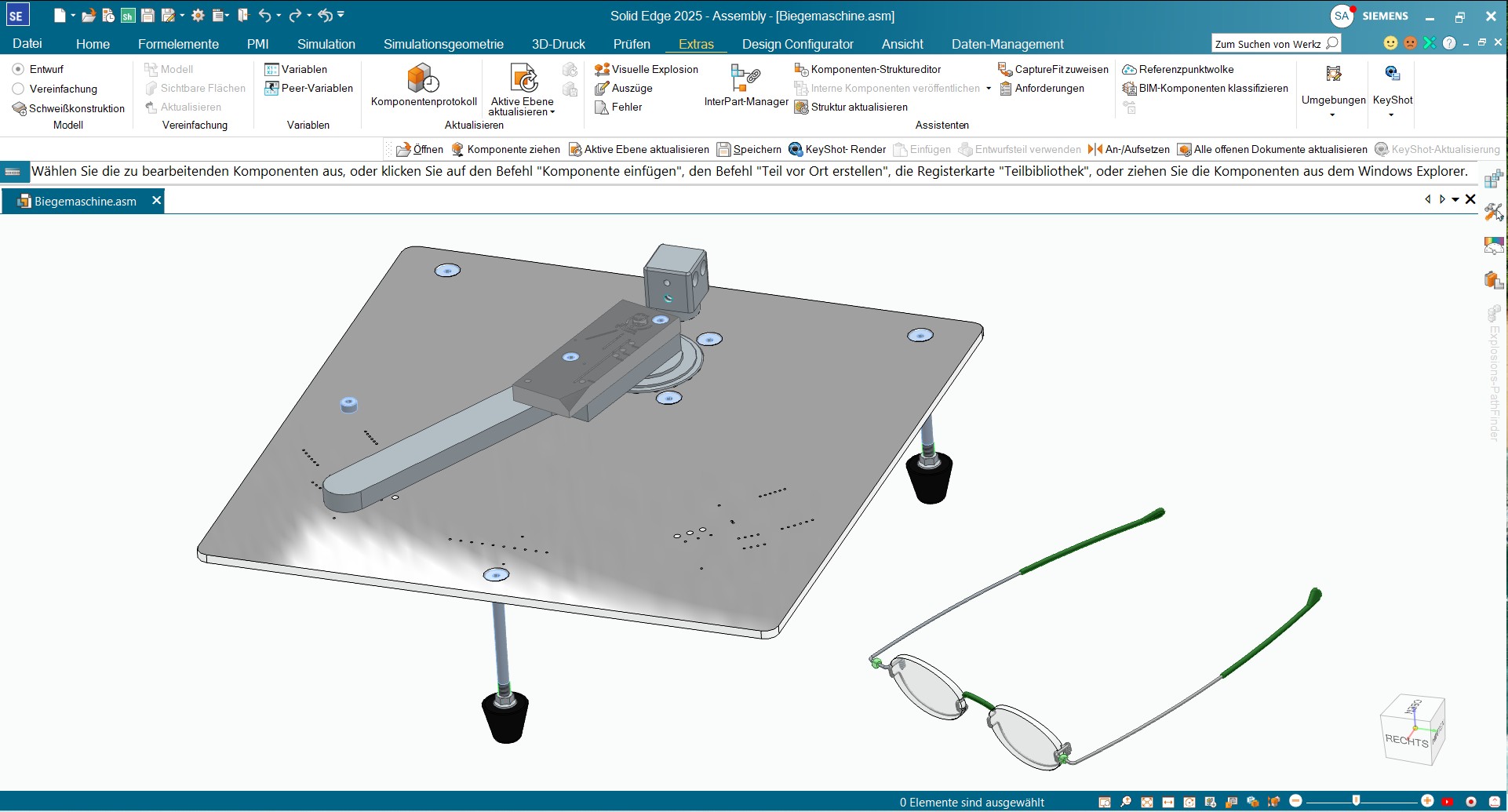

To achieve this level of repeatability and reliability, GoodVision used Designcenter Solid Edge from Siemens to develop their frame-bending device as well as the glasses. Aufmuth had been part of a school that was partnered with Siemens, so the transition from using the software in education to using it for philanthropic ventures was obvious. Now the organization uses Solid Edge X Premium. GoodVision also receives support from their Siemens Solution Partner, Var Group, who assisted the organization with joining the Siemens’s start-up program, and continues to provide professional support for any user issues with Solid Edge.

Leveraging Solid Edge has allowed volunteer engineers to build, refine and test designs digitally long before they reach the field. It also ensures that every component, from the frame hinge to the tiny locking fit of the lens interface, can be manufactured with the precise tolerances required for medical equipment, even in the field.

“It’s a medical product, so we have to test the glasses,” Adams explains. “For example, the insert is set up in a special way so that they always fit and we have to have certificates for that. And in some countries, we are not allowed to sell the complete glasses without certification. To get the certifications needed, we had to provide all the designs, the drawings of everything with tolerances. You need to provide how you test your product afterwards, so we not only designed the machine, we also designed tools to test our product and tools for additional tasks.”

The organization has now gone through five major generations of the bending machine. Each version focuses on refining ease of use, cost efficiency and manufacturability. Sometimes progress means tighter tolerances. Other times it means widening them to reduce costs without sacrificing function or certification.

Precision in the Field

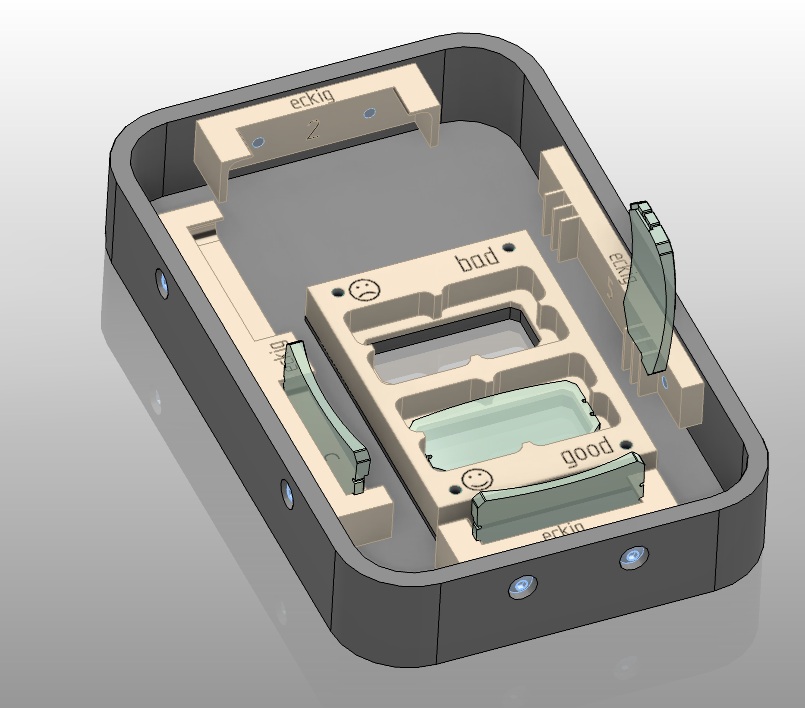

GoodVision has now supplied more than a million pairs of glasses worldwide in countries such as Burkina Faso, Nepal, Brazil and India, just to name a few. But scaling also requires quality control, especially when it comes to medical equipment. Lenses are sourced from overseas manufacturers, and each shipment must be inspected to ensure consistent fit with the frame system. To make this process volunteer-friendly, the organization designed physical go/no-go testing gauges that indicate whether the lenses meet required specifications without requiring calipers or specific technical training.

Turning precision engineering into repeatable, human-centered workflows is where GoodVision has really taken hold.

The organization intentionally does not give glasses away for free to most adults. Charging the equivalent of one to three days’ wages ensures that the glasses carry value, supporting dignity rather than dependency. For schoolchildren, the glasses are provided at no cost because GoodVision views education as a foundational form of economic opportunity. That’s why they have developed this pricing structure to be thoughtful, culturally sensitive and rooted in long-term sustainability.

Scaling Across Continents

GoodVision now operates in multiple regions across Africa, India and South America. The challenge ahead is not just engineering, it’s adaptation. Each region has its own cultural norms, logistical realities and operational landscapes. Ensuring consistent standards across different countries while maintaining local autonomy is one of the organization’s most significant ongoing efforts.

Yet the mission remains to empower communities to produce glasses locally, using local hands, for local needs. That’s why the organization is looking to continue to grow in a number of ways. “Right now we have three different sorts of glasses, and we are looking into more of the design,” Adams says. “There’s a lot to develop at that point. We also want to continue to make the testing easier, when the frames are done, to really do the quality check.”

GoodVision reminds us that engineering is not just about designing products. It’s about designing systems that remove friction, empower communities and honor human dignity. And sometimes, the most powerful tools are the simplest ones.

To learn more, visit Designcenter Solid Edge from Siemens.