Drexel and McGill engineers turn proboscides into high-resolution nozzles.

Here’s my first hot take of 2026: mosquitos are terrible.

They’re responsible for almost 700 million infections and over a million deaths every year. Plus, they’re seriously annoying when you’re trying to sleep. I’ll gladly go on record as being stridently anti-mosquito, but now I must also grudgingly admit that they have at least one potential upside thanks to a team of engineers at McGill University and Drexel University.

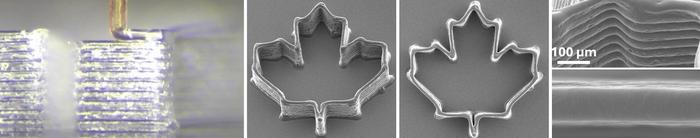

Working together, these researchers have found a way to turn female mosquito proboscides into nozzles for high-resolution 3D printing, resulting in printed line widths as fine as 20 microns, which is roughly half the width of what commercially available nozzles can achieve.

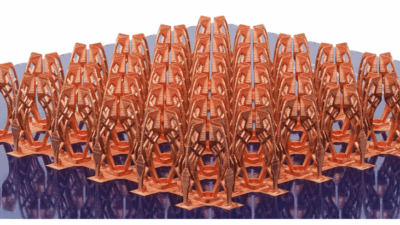

The engineers have dubbed their approach “3D necroprinting” (my first new term added to Word’s dictionary this year) since it incorporates non-living biological microstructures (i.e., the proboscides) direct into the printing process. Potential applications of 3D necroprinting include the production of scaffolds for cell growth and tissue engineering, cell-laden printed gels, and transportation of microscopic artifacts, such as semiconductor chips.

“High-resolution 3D printing and microdispensing rely on ultrafine nozzles, typically made from specialized metal or glass,” said study co-author Jianyu Li, in a McGill press release. Li is an associate professor and Canada Research Chair in Tissue Repair and Regeneration at McGill. “These nozzles are expensive, difficult to manufacture and generate environmental waste and health concerns.”

“Mosquito proboscides let us print extremely small, precise structures that are difficult or very expensive to produce with conventional tools,” added Changhong Cao in the same release. “Since biological nozzles are biodegradable, we can repurpose materials that would otherwise be discarded.” Cao is an assistant professor and Canada Research Chair in Small-Scale Materials and Manufacturing as well as a co-author on the study.

The study was led by McGill graduate student Justin Puma, who was involved in a previous study using a mosquito proboscis for biomimetic purposes that established a foundation for this research.

Probing the limits of high-resolution 3D printing

To develop the nozzles, the researchers examined insect-derived micronozzles and identified the mosquito proboscis as the optimal candidate. The proboscides were harvested from euthanized mosquitoes, sourced from ethically approved laboratory colonies used for biological research at Drexel.

Under a microscope, the researchers carefully removed the mosquito’s feeding tube before attaching it to a standard plastic dispenser tip using a small amount of resin. The researchers characterized the tips’ geometry and mechanical strength, measured their pressure tolerance, and integrated them into a custom 3D-printing setup.

Once connected, the proboscis becomes the final opening through which the 3D printer emits material. The researchers have successfully printed high-resolution complex structures, including a honeycomb, a maple leaf and bioscaffolds that encapsulate cancer cells and red blood cells.

“Evolutions in bioprinting are helping medical researchers develop unique approaches to treatment. As we look to improve technology, we must also strive to innovate,” said Megan Creighton, in the same release. Creighton is a co-author and assistant professor of chemical and biological engineering at Drexel.

“We found the mosquito proboscis can withstand repeated printing cycles as long as the pressures stay within safe limits. With proper handling and cleaning, a nozzle can be reused many times,” Cao said.

“By introducing biotic materials as viable substitutes to complex engineered components, this work paves the way for sustainable and innovative solutions in advanced manufacturing and microengineering,” Li said.

The study is published in the journal Science Advances.