Fabric8Labs defies many 3D printing conventions, and that could be the key to its success.

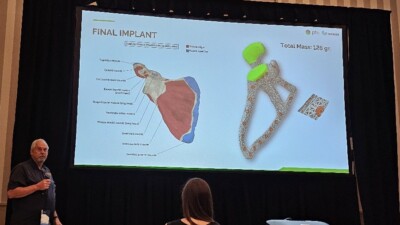

Example of a phased antenna array on a PCB created with electrochemical additive manufacturing. (IMAGE: Fabric8Labs)

“He will win who knows when to fight and when not to fight.”

– Sun Tzu, The Art of War

There are a lot of ways to interpret this little piece of ancient wisdom but, when it comes to additive manufacturing (AM), I think the best way is to take it as equivalent to the much more modern aphorism: Stay in your lane. It’s taken the 3D printing industry almost four decades to figure out what that lane looks like and, thus far, it doesn’t appear to include a big off-ramp for volume production.

Look for AM’s victories and you’ll find them in prototyping, in manufacturing support, and in end-use applications where customization or complex geometries (which often amount to the same thing) take priority over speed and cost, i.e., medical or aerospace. The reasons for this are well worn, but they’re also based on a certain set of assumptions about what additive manufacturing looks like and how it works.

After a recent conversation with Fabric8Labs VP of product and applications, Ian Winfield, I’m starting to wonder whether winning in AM is less about fighting the right battles or staying in the right lane, than it is changing the rules of the game altogether or (with one last twist of the knife into this tortured metaphor), straying off the beaten path.

Yes ECAM

Winfield doesn’t have the typical background of an additive manufacturing expert. Rather than coming from medical or aerospace or mechanical more broadly, his formal training is in electrochemistry. But there’s a good reason for that. “When I saw what Fabric8Labs was doing in terms of using electrochemistry for 3D printing structures, it sort of blew my mind,” he tells me. That’s because, while most engineers probably think of using electrochemistry for thin films in, for example, electroplating, Fabric8Labs has found a way to use it to build three-dimensional objects. This is what the company calls Electrochemical Additive Manufacturing (ECAM).

Essentially, in ECAM the entire build plate is the cathode. As Winfield explains it:

“We generally integrate the build plate into the final product. So, if you think about liquid cooling, we can procure a 1-2mm thick sheet of copper 101 and then chemically activate it. It gets chucked into the Z stage on the top, and the bottom – the printhead – is based on display technology. We bring the build plate down to that display and then send the pattern of what we’re printing to activate it. Wherever we activate it, that creates an electric field, so I envision it as projecting an electric field wherever I activate a pixel.”

Clearly, this is a very different approach to 3D printing metals compared to laser powder bed fusion (L-PBF) or directed energy deposition (DED) for several reasons. First and foremost, while those processes often struggle with pure copper due to its reflectivity, that’s the primary material for ECAM. Moreover, the feedstock itself is a metal oxide, which can be pumped through multiple machines and is both less expensive and considerably easier to handle than metal powder.

Then there’s the resolution, which is extremely high: Winfield says ECAM’s voxel size is currently 33μm. Together, these attributes point to electronics and thermal management as ideal applications for ECAM.

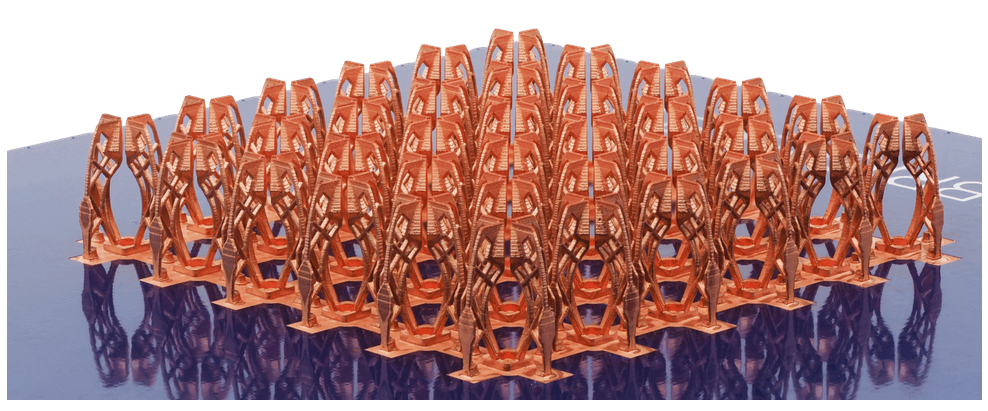

Of course, one thing ECAM shares in common with other additive technologies is that its high resolution comes at the price of a relatively small build volume: Winfield says the display (which dictates ECAM’s build volume) is currently 120mm x 120mm and that the machine’s output is 1-2mm per hour in the Z-axis, but he also added that scaling up ECAM is relatively simple in terms of connecting additional machines to the feedstock plumbing.

“We’re grouping them today in our facility in what we call a ‘pod’ of 24 printers with one feedstock system that’s pumping liquid to all of them,” he says. “If we wanted to increase the build area, we’d just have to make sure we re-engineer the tool to make sure we’re holding everything planar, because we’re working in such close layer heights.”

Technology-Market Fit

“Everyone talks about product-market fit,” says Winfield, “but I think a lot about technology-market fit: the intersection between what’s best for the manufacturing technology and what’s best for the end product.” For ECAM, that line of thinking goes straight to thermal management and electronics, including 3D printed antennas, which can actually be printed directly onto PCBs, since the process runs at room temperature. An added bonus, Winfield points out, is that since the print head in ECAM is controlled via lithography, all the antennas in a phased array come out perfectly aligned.

Beyond electronics, ECAM also has potential in medical device applications, such as x-ray collimators or minimally invasive surgical tools. “We’ve already done testing with a nickel-cobalt alloy that we’ve developed for biocompatibility,” Winfield explains. “You wouldn’t use that for a permanent implant, but as a surgical tool, the alloy we developed meets FDA requirements.” He also mentioned micro-mechanical components, electrical connectors, and power electronics – such as traction inverters for electric vehicles – as other potential avenues where the technology could expand. This is, notably, another way in which ECAM seems different from other additive technologies: 3D printing often seems like a solution looking for problems but, as Winfield frames ECAM, the challenge appears to be limiting the scope of R&D into various applications to ensure Fabric8Labs is growing in the right way.

To that end, the company just completed a major funding round: $50M to expand its domestic advanced manufacturing capacity. That level of investment in AM isn’t as common as it used to be when 3D printing hype was at its peak, and it’s especially surprising given how much focus (and funding) artificial intelligence (AI) draws these days. When I mentioned this to Winfield, he pointed out that AI is actually a good thing for Fabric8Labs in terms of market potential.

“Liquid cooling has been around for 20 years, but not at scale in data centers by any means,” he explains. “With these high-powered GPUs, everyone’s saying, ‘Oh my gosh, I’m going to have to go from 5% liquid cooling to 95% liquid cooling in my data center,’ because that’s the only way to get the GPU density they need, so the timing of the AI boom has really helped us in that way.”

“If fighting will not result in victory, then you must not fight”

Much of the discussion around AM today involves how best to deal with two of the biggest obstacles for scaling it: post-processing and quality control. Yet what’s interesting about Fabric8Labs is that the company seems to be building an additive technology that simply avoids those challenges rather than confronting them.

Winfield says that common post-processing techniques for metal AM (heat treatments, powder or support removal) are unnecessary in ECAM: “All we do is run the part through a couple of rinse tanks to make sure there’s no residual chemistry and then passivate it to make sure the copper doesn’t oxidize.”

In-situ monitoring, a much sought-after feature for practically all AM processes, also comes almost for free in ECAM. “If you think about Ohm’s law, that enables us to detect the proximity of a copper feature to a pixel, so we can generate a heat map of how each layer is progressing over the build,” Winfield explains. “Then there’s an algorithm that can turn the pixels on or off, or turn the current density up or down, because we have grayscale control over individual pixels. And what’s really cool is you can use that data to recreate the part – almost like an x-ray scan – and see how well it built and if any features are missing. Our goal is to eventually use that data to say whether the part is good or bad even before it comes off the printer.”

It’s easy to get caught up in the excitement of a new technology, and I’ll freely admit that I am excited about ECAM and what it could mean for the future of additive manufacturing as an industry. Of course, with how often this industry has been burned by excessive hype, it’s prudent to be conservative in predicting where this technology is heading. Still, if I were a betting man, I wouldn’t bet against Fabric8Labs.