The story of how PTC and Hexagon came together with Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center to 3D print a new scapula for a 16-year-old girl.

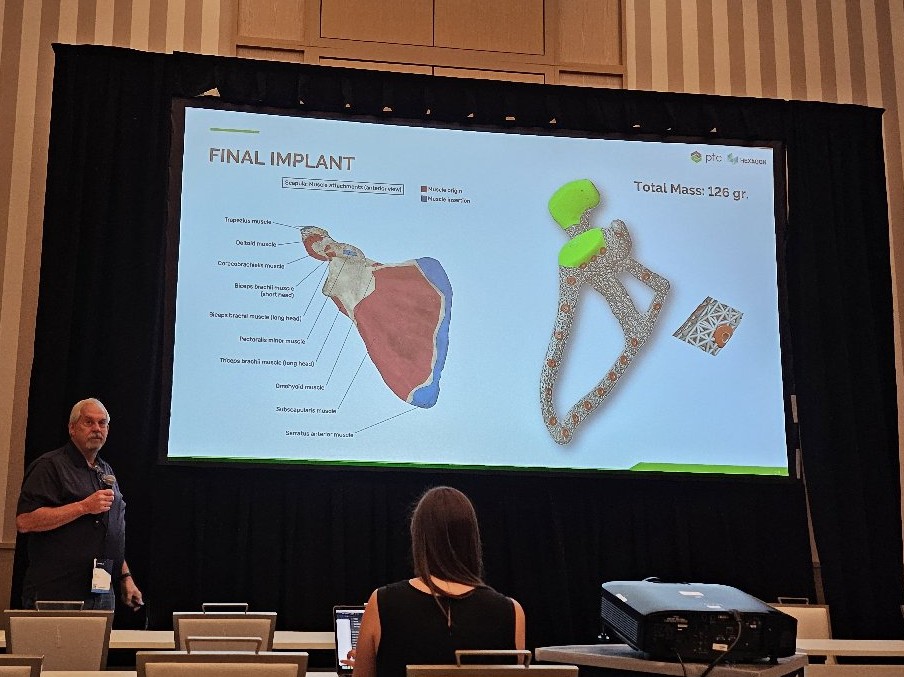

The final design of a 3D printed scapula implant, showcased at Hexagon LIVE 2025. (IMAGE: Author)

The word ‘transformative’ is bandied about quite a lot when it comes to 3D printing. We’ve been told that it will revolutionize construction, that it’s the evolution of manufacturing driving scalable customized production. Under the right conditions, the future of this technology is limitless, supposedly. But, really, isn’t this all just marketing hype?

Honestly, 3D printing, you really need to start acting your age.

You’re over 40, for goodness’ sake!

This talk of transformation seems wildly optimistic, especially after all the failures we’ve seen in this industry. And yet, and yet: there are cases where additive manufacturing (AM) is undeniably transformative, most obviously in medical applications. Here’s a paradigm example I came across at this year’s Hexagon LIVE.

A life-changing engineering challenge

Think back to when you were sixteen years old.

For most of us in the developed world, it’s a challenging age but only in the relatively banal sense of adolescent struggles: school, social cliques, dating. For one girl in Israel, however, the challenge included Ewing’s sarcoma, a rare cancer causing bone degeneration that resulted in considerable pain and discomfort, as well as severe swelling in her right shoulder. Her scapula – the large bone that essentially encircles the arm joint where it connects with the rest of the body – was afflicted, and because it connects to so many muscles, it’s crucial not only for mobility but also quality of life.

“This whole project was about what we can do to make this girl’s life better,” explains Lee Goodwin, solutions consultant at PTC. “Our goal was to keep the same shape and general size of the bone, but replace it with something we engineered. That meant we needed to look at the kinematics as well as the mechanics and ensure it could attach to all those muscles.”

To do that, Goodwin and his colleagues at PTC, Hexagon, and Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center collaborated on 3D printing a titanium implant. Titanium is a common go-to for such implants, but there were challenges that came with using it to create such a large one, as Goodwin explained. “You’ve got to understand: Is it going to be strong enough? Is it going to weigh too much? Titanium is three times denser and its stiffness is four times greater than bone, which means it doesn’t have to be as big as the original bone as long as it can still attach to everything.”

They started with MRI scans of the intact left scapula and mirrored it to generate a model of what the right scapula should look like. The team then brought that data into a CAD platform (in this case, PTC’s Creo) to adjust the model, removing material to reduce weight and creating anchor points for muscle tissue. The result was a design that would serve the same function as the natural bone with a lattice structure to reduce weight further as well as encourage tissue growth. Goodwin says they used Creo’s analysis capabilities to test loads and deformations based on expected stresses.

Will it print?

Design freedom is one of the chief benefits of using 3D printing, but it often belies the difficulties of the 3D printing process itself. As Mathieu Pérennou, director of AM solutions at Hexagon puts it: “All the work that has been done to match the weight, the center of gravity, the dynamics of the implant, that doesn’t guarantee it’s going to print okay.”

To do that, Pérennou and his colleagues at Hexagon took PTC’s design and used their software to optimize its orientation in printer, including support structures, and then generated a file for the 3D printer. But before actually printing from that file, the team took the intermediate step of simulating the entire process via digital twins. By inputting not only the file but the material and process parameters, Pérennou and his team were able to predict shrinkage during the build and compensate the nominal geometry to ensure the part would be within tolerance.

“We can do all that without any physical iterations,” Pérennou says. “And that’s actually a lot faster—printing virtually on a computer—than doing a physical print.”

Post-processing and inspection

As anyone who’s worked with 3D printing knows, parts never come finished straight out of the machine, especially metal ones. That certainly applies in this case, where the printed scapula required finishing as well as polishing of the contact surfaces. After that comes another crucial step: inspection. “You don’t want to risk putting in an implant that will break because of porosities,” explains Pérennou, “so we did a CT scan and analysis of the part using VGStudioMax, looking for powder entrapment or porosities. We compared what was actually printed with the nominal, and then it’s up to the surgeon to decide whether it’s close enough to use the implant.”

One interesting sidenote is that the implant is too strong, it can actually weaken everything around it as the body adapts to it. As a result, it can actually be preferable to err on the side of weakness rather than strength when it comes to permanent titanium implants such as this.

The biggest takeaway from this project, however, is the speed at which it was executed.

“What we managed to do in four days,” Pérennou says, “is scan the patient, design an implant, print it, and implement it. We were aiming to do this in the shortest amount of time possible.” The ability to shorten lead times is another oft-touted benefit of 3D printing, but in this case—4 days for an implant that will impact the rest of this patient’s life—it’s truly inspiring.