On the question of AI versus expertise in the DfAM discussion panel at Formnext 2025.

I’m so tired of hearing about AI.

Maybe it’s because I grew up watching and reading science fiction, and the idea of real artificial intelligence always seemed even more exciting to me than space travel. Forget warp drive, I wanted to be able to have a conversation with a computer.

Now I can, but I also can’t trust it and using it carries untold environmental, economic, and sociological costs. Add to that disappointment the fact that “AI” is being crammed into every nook and cranny of our technological lives (despite near-universal protestations by consumers) and fatigue appears not only understandable, but inevitable as well.

I keep hoping the bubble will pop or, preferably, gently deflate.

Until then, we’re faced with questions like, “What does AI mean for design for additive manufacturing (DfAM)?” which was more or less the theme of a panel discussion at Formnext 2025.

Moderator Frank Jablonski sat down with four experts to talk about the juxtaposition between the ease with which 3D printing makes creation possible and the difficulties of understanding the materials, process limits, and performance necessary to succeed in additive manufacturing (AM). One of the key takeaways from that discussion is that software—including AI—is no replacement for hands-on experience.

Here’s why.

Shape-making vs design

Jonathan Rowley, steering committee member of the UK’s Design for AM Network and CEO of Additive Companion, sets the tone early on by making a distinction between simple “shape-making” and actual design, which he says includes materials as well as the context of the part being designed.

“There’s nothing wrong with shape-making,” he says, “but if you can make shapes that then perform, that’s when you’re really starting to design and take this to a whole new level.”

Tobias Hehenwarter, CEO of the German engineering firm ID Design, agrees with Rowley on the importance of process knowledge and the role in plays in the “decision tree” one has to follow from CAD file to 3D printed part. However, he takes this even further by stating that, in the long-term, DfAM means designing objects that couldn’t have been imagined without an understanding of AM. “I’ve seen water taps that have the weirdest kind of shape,” he explains, “and you don’t understand where the water is coming from. It just looks like a solid piece of metal, but it’s enabled because the designers understood the 3D printing process in detail: how the metal is molten, how the depowdering process works, and so on.”

AM-azon?

The suggestion that DfAM requires this level of understanding raises questions about the possibility of an “Amazon-like” marketplace, where users can select a combination of design, material, and provider, to order highly customized products. However, as David Nguyen, senior technical services engineer for PTC’s Onshape, points out, that model has been tried by Shapeways, with poor results when what’s ordered diverged from the best technology to see it through.

In response, Rowley brings up the idea of co-creation, where customers can influence designs through collaborations with customers. That seems agreeable to Hehenwarter, who once again emphasizes the importance of 3D printing’s unique value proposition in delivering parts that are only possible via AM. Nevertheless, the panelists also agree that the sorts of fun hobbyist projects available through online models can be a good entry point for future additive manufacturing engineers.

Print settings as a design tool

This point brings up a fundamental distinction between the users of 3D printing: engineers operating in industrial environments (whether for tooling, prototyping or end-use parts), and hobbyists who engage with the technology simply because they’re passionate about it. While it’s tempting to treat these two groups as entirely separate, Sophia O’Neill, founder and creative director of the 3D printed fashion company NURBS by Dapna, argues that professional engineers should not discount the amateur enthusiasts.

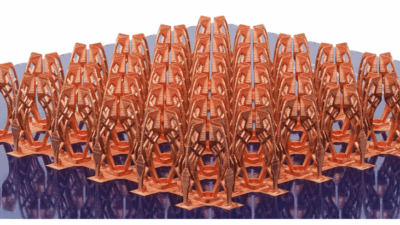

“We can learn so much from these hobbyist printers,” she says. “in shape, in articulation, even material usage. Jonathan talked about shape-making, but when you make a shape that complements a material so that it behaves in a certain way, it’s perfect.”

O’Neill also notes that, “My biggest tool is print settings…especially working with filaments and materials that behave in a specific way.” As an example, she explains how wall thickness can be used intentionally to control surface effects, such as color swirls and gradients. Nguyen adds that the kind of color distributions exhibited in the example pieces she references would be difficult to injection mold without complex, multi-shot strategies.

Collaboration and its limits

Shifting the discussion from objects to organizations, Nguyen highlights the challenge that comes with designers, prototype makers, and production teams often operating in semi-isolation and with limited feedback between them. Obviously, there’s an incentive here for him to point to cloud-native CAD solutions (i.e., Onshape) as a solution—and he does—but beyond that he emphasizes the importance of having a foundational, process-aware approach to DfAM.

“We need to adapt our knowledge to the specific additive manufacturing technology we’re working with and design toward that,” he says. “SLS has a lot of design freedom, but you need to design for SLS to reach the full potential of that technology.”

Rowley chimes in that he learned about SLS from hands-on experience accumulated over nearly a decade, and that generic service bureau design guidance that focuses on basic issues like minimum wall thickness bely the complexity of AM processes. “Designing for AM is like designing for anything,” he says, “It’s about experience, understanding materials, knowing what you’re working with. When I hear about ‘democratization of design’, I find that a bit of an insult.”

Hehenwarter agrees wholeheartedly: “You really have to understand the whole process, and there’s no way around that. At the moment, you cannot use AI. The designer has to understand the technology they’re designing for and the engineering involved, and they have to test it for themselves.”

AI’s place in AM

And now we come to it: once someone says “AI” in a setting like this, everyone has to talk about it. Moderator Frank Jablonski asks the panelists whether and to what extent they use AI in their own work.

O’Neill has a pragmatic stance, using it for cost-saving business needs, such as generating product photo shoots and marketing proposals. Nguyen seems more optimistic about AI’s potential as a research assistant or providing design review, flagging potential issues when using a given process.

Hehenwarter pushes back on this point, however, saying that AI is too unreliable to be used for anything more than inspiration. Rowley jumps in even more forcefully: he believes AI is “years away” from doing what Nguyen imagines and warns that applying AI to AM now just results in recycling shallow, received wisdom rather than building reliable, experience-based guidance.

At closure of the discussion, O’Neill offers a concrete example of how she believes AI can be useful to AM: failure detection. “It’s great in both large-scale and small-scale additive manufacturing,” she says. “That loop is one of the best implementations of AI in this industry. And yes, of course, it’s scary and there’s a lot of discussion around that side of AI implementation, but I do love a good failure detection.”

“Sophia,” Rowley replies, “I’m not scared of it: it’s just bad.”