Fast-curing concrete, blood vessels on a chip, micro delta robots and more!

Composite SEM image of microDelta robots (IMAGE: Carnegie Mellon University.)

Thanksgiving is almost upon us and we all know those topics that will inevitably come up at the dinner table despite ever present reminders to avoid them. But here’s one topic you won’t find on that list: 3D printing.

So, when your relatives start expounding on their own pet theories of “What’s Wrong With This Country” or “The Trouble With Kids Today” why not derail them with anecdotes about some of the latest breakthroughs in additive technology?

Here’s a few to get you started:

Mighty Morphin 3D printed structures!

We’ve covered the topic of 4D printing for years here on engineering.com, but the technology still largely confined to the laboratory. However, a team of engineers from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign is aiming to change that with a new approach to morphing 3D printed two-dimensional structures into curved 3D structures for space-based applications.

“[O]ur collaborators in the Beckman Institute developed a recipe for a pure resin system that’s very energy efficient,” explained Ph.D. student Ivan Wu in a press release. “And we have a 3D printer that can print commercial aerospace-grade composite structures. I think the breakthrough was combining those two things into one.”

Wu’s idea is to mold the liquid resin with printed carbon fiber and then freeze it, so that it can be stored safely and efficiently for transport and then later activated via a low-energy heat stimulus that initiates the polymerization process. This process, called frontal polymerization, is intended to eliminate the need for ovens or autoclaves large enough to cure a full-sized satellite dish.

“For me, the first challenge was to solve the inverse problem,” Wu said. “You have a design for the 3D shape you want, but what is the 2D pattern to print that results in that shape? I had to write mathematical equations to describe the shapes to print the exact pattern. This study solved that problem.”

Wu sourced equations and wrote the code to program the printer to deposit the fiber bundles onto a bed to create five different 3D configurations: a spiral cylinder, a twist, cone, a saddle and a parabolic dish.

“Together, they show the diversity of shapes we can make. But I think the one that’s most interesting and applicable is the parabolic dish, which mimics the smooth, curved shape that’s needed for deployable satellites.”

Wu’s proposal is to use the activated 3D shapes as molds for in-space manufacturing of high-stiffness structures. His research is supported by the Air Force Research Laboratory and published in the journal Additive Manufacturing.

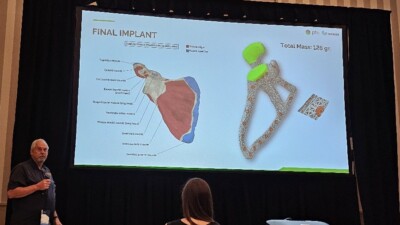

microDeltas of the world, unite!

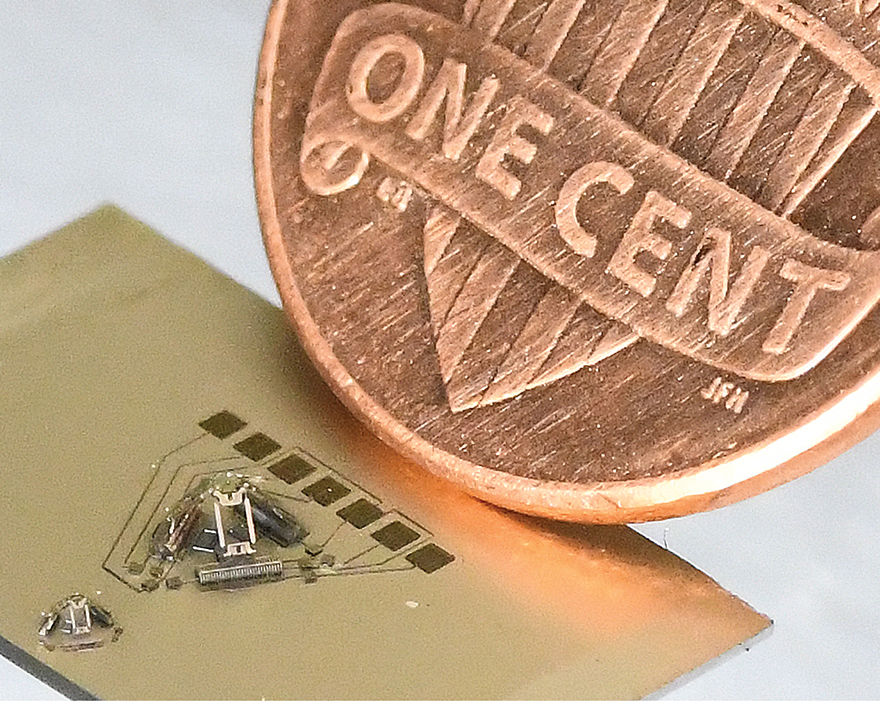

Another well-worn topic on our site, delta robots have been deployed in all manner of picking, packing, and sorting tasks in a variety of manufacturing industries. They’re typically on the order of a few cubic feet in size, but a team of engineers at Carnegie Melon University have managed to 3D print “microDeltas” that make a penny look enormous.

Microrobotics at this scale have normally required manual assembly and folding microfabricated components, but the Carnegie Melon engineers have developed a 3D printing process for microrobotics that uses a combination of two-photon polymerization and a thin metal coating to create complex 3D geometries and actuators without any folding or manual assembly.

“Eliminating the need for assembly has huge benefits in terms of rapid fabrication and design iteration,” said Sarah Bergbreiter, professor of mechanical engineering at Carnegie Melon, in a press release. “At large scales, researchers can assemble robots from motors and mechanisms that you can buy off-the-shelf. We don’t have that luxury at these small scales where both making and connecting tiny pieces together is hard. That’s where this new fabrication process is incredibly beneficial.”

According to Bergbreiter and her students, the 1.4 mm and 0.7 mm microDeltas, are the smallest and fastest Delta robots ever demonstrated. They also claim that shrinking the robot improved precision to less than a micrometer, increased speed by operating at frequencies over 1 kHz, and delivered enough power to launch a grain of salt: a projectile 7.4% the mass of the entire robot.

They suggest that densely packed arrays of multiple microDelta robots could enable entirely new robot capabilities at small scales, such as rich haptic feedback or previously infeasible micromanipulation tasks.

3D printed blood vessels while you wait

3D printing organic tissue, aka bioprinting, has been used to duplicate brains, bones, cartilage, and ligaments, sometimes not just replicating but improving on nature’s designs. The latest advancement in this vein (pun unintended but grudgingly preserved) comes from mechanical and biomedical engineers at the University of Sydney.

They’ve created anatomically accurate models of both healthy and diseased areas of blood vessels, including their delicate structures and the dents and divots on the damaged lining of the blood vessel walls that are commonly found in stroke patients.

The researchers used CT scans of stroke patients as blueprints to create mini models, shrinking the original 5-7mm carotid artery 3D model to 200 to 300 micrometers. They also managed to reduced the time it takes to print the models from 10 hours to two by using glass slides as a base, rather than the conventional resin moulds.

According to the team, this artery on a chip’ method successfully mimicked the physical appearance of blood vessels, and blood flow simulations generated similar fluid dynamics and movement of natural blood flow. During testing, the researchers were able to witness, in real time and under the microscope, blood clot formation and the behaviour of platelets which area crucial component involved in blood clotting that could lead to a stroke.

“We’re not just printing blood vessels,” said PhD candidate Charles Zhao, “We’re printing hope for millions at risk of stroke worldwide. With continued support and collaboration, we aim to make personalised vascular medicine accessible to every patient who needs it.”

The research is published in the journal Advanced Materials.

She’s a quick (3D printed) house

Closer to home, researchers at Oregon State University have delivered the latest advancements in 3D printing for construction with a quick-setting, sustainable alternative to concrete that they’re hoping could be used to 3D print homes and infrastructure.

The new clay-based material cures as it’s being extruded as a result of an acrylamide-based binding agent triggering frontal polymerization. The researchers report that their material can even be printed across unsupported gaps, such as the top edge of an opening for a door or window.

“The printed material has a buildable strength of 3 megapascals immediately after printing, enabling the construction of multilayer walls and freestanding overhangs like roofs,” said Devin Roach, assistant professor of mechanical engineering in the OSU College of Engineering, in a press release. “It surpasses 17 megapascals, the strength required of residential structural concrete, in just three days, compared to as long as 28 days for traditional cement-based concrete.”

Additionally, because the new material consists largely of soil infused with hemp fibers, sand and biochar – carbon-rich matter made by heating wood chips and other organic biomass under low oxygen – its environmental footprint is significantly smaller than that of concrete.

“Currently, our material costs more than standard cement-based concrete, so we need to bring the price down,” Roach said. “Before it can be used we also need to follow American Society for Testing and Materials standard tests and prepare a report that professional engineers can review and approve if it is proposed to be included in construction projects.”

The research is published in Advanced Composites and Hybrid Materials.

That’s it for this Thanksgiving Research Roundup. Enjoy your turkey and be thankful it was raised on a farm instead of in a vat!