Multi-material 3D printing enables new approach to cyborg insects.

From a hobbyist perspective, the collision between Halloween and 3D printing seems inevitable, with dozens of costume ideas and STL files available online, not to mention the slightly more ambitious projects for those with the requisite design skills.

Of course, we aspire to go beyond 3D printing as a hobby here at engineering.com but with the ongoing government shutdown, we can’t count on NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory to continue its annual tradition of pumpkin carving with an engineering twist.

What’s a lowly senior editor to do on All Hallows’ Eve 2025?

At the eleventh hour (more or less), it’s Nanyang Technological University (NTU) in Singapore to the rescue with 3D printed costumes for cockroaches!

Okay, that’s a bit of a misrepresentation. Technically, what we’re talking about is a new approach to creating cyborg insects using multi-material 3D printing. Odd as it may sound, cyborg insects are not a novel concept, but there are issues with the conventional way of doing it, which typically involve cutting sensory organs or using adhesives.

“The methods have flaws,” explained Hirotaka Sato, coauthor the published research, in a press release. “Invasive implantation irreparably damages sensory organs, reducing the insect’s ability to detect obstacles and navigate. Adhesive-based films degrade over time, cause exoskeleton harm during removal, and require skillful application—extending preparation time and limiting reuse. Ethically, cutting appendages violates the ‘3Rs’ framework (Replacement, Reduction, Refinement) for humane animal research, raising concerns about animal welfare.”

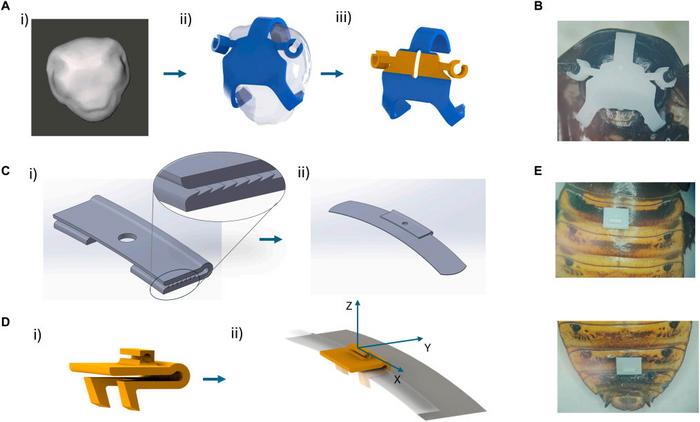

The researcher’s alternative approach consisted of two “wearables” to create cyborg insects: headgear for antenna stimulation and abdominal buckles for acceleration control.

(IMAGE: Hirotaka Sato, School of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, Nanyang Technological University.)

The headgear uses C-shaped elastic connectors that expand during attachment and then contract to grip the base of the antennae as well as triangular hook anchors that are designed to latch onto a cockroach’s head without hindering its movement or ability to feed.

The abdominal buckles, which attach to the insect’s second and sixth segments, consist of U-shaped clamps and gripping hooks, with an overall structure that mirrors the cockroach’s natural points of articulation.

“To create these intricate, functional devices, we used digital light processing (DLP)-based multi-material 3D printing and selective electroless copper plating—technologies that enable precise control over conductive and nonconductive regions,” the researchers wrote.

They also claim that their tests on Gromphadorhina portentosa (Madagascar hissing cockroaches) showed stable neural responses, precise motion control, accurate S-path navigation, and strong obstacle negotiation. Apparently these particular roaches are a common choice as the biological half of a cyborg insect due to their relatively high load-bearing capacity.

“The noninvasive design preserves the insect’s natural sensory capabilities, which is game-changing for real-world use,” Sato said in the same release. “This work moves cyborg insects from lab demonstrations to scalable, practical tools in robotics and biohybrid systems.”

The research is published open-access in the journal Cyborg and Bionic Systems.