Why there’s more to it than composting PLA.

Sustainability matters more than ever these days, and it crops up everywhere in engineering, from specific concerns in the aerospace industry to digital transformation more broadly, even in conversation with the founder of Onshape.

In the context of materials for additive manufacturing (AM), sustainability generally amounts to two factors: recyclability and biodegradability. On the former topic, there’s plenty of good work being done (with some applications you might not expect), but when it comes to whether and which 3D printing materials are biodegradable, the waters tend to be a bit murkier.

So, here’s a brief rundown of what you need to know about biodegradable materials in 3D printing.

Is PLA biodegradable?

The short answer is, “Yes, polylactic acid (PLA) is biodegradable.”

The longer answer is that PLA is a bioplastic, with its lactic acid or lactide monomers originating from fermented plant starch, and hence its rate of degradation varies by isomer. Consequently, the most effective means of degrading PLA in general is via industrial-grade composters operating at temperatures in excess of 60°C.

Additionally, although PLA degrades primarily through hydrolysis, experiments have demonstrated that it takes over a year to degrade in marine environments. This suggests, as the researchers in the previously linked paper conclude, that PLA should be more accurately represented as compostable, rather than biodegradable.

Perhaps more to the point, even if PLA were unambiguously biodegradable, its usefulness in the context of 3D printing tends to be limited to prototyping at the concept, form, and fit stages. In other words, it’s not a robust material candidate for end-use AM parts, which is also where the biggest impacts on sustainability will be found.

Other biodegradable 3D printing materials

Besides PLA, the polymer most often cited as a biodegradable material option for 3D printing is polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA). Like PLA, it’s produced via bacterial fermentation of sugars or lipids, but with a much larger range of viable monomers, resulting in a wide variety of materials, including both thermoplastics and elastomers. Additionally, unlike PLA, PHA also has the advantage of being UV stable, making it more durable. Some PHAs have even been compared (favorably) to polypropylene (PP) in terms of their material properties.

Research on PHA degradation has shown that these polyesters are completely biodegradable, especially in marine environments. This puts them well ahead of other bioplastics, including PLA, in terms of their sustainability. Additionally, while filaments are by far the most common form of PHAs for extrusion-based 3D printing processes, there have also been reports of successfully using PHA powders in selective laser sintering (SLS).

Other biodegradable materials with AM potential include naturally occurring polymers, such as alginate, cellulose, and collagen, as well as natural fibers such as bamboo, flax, and hemp. There’s also at least one example of engineers 3D printing packaging materials using coffee grounds and mushroom spores.

All of these naturally derived materials offer tantalizing possibilities for further improving the sustainability of AM; however considerable research efforts are still needed to advance the technology to be ready for industrial and commercial implementations.

Why biodegradable materials matter in 3D printing

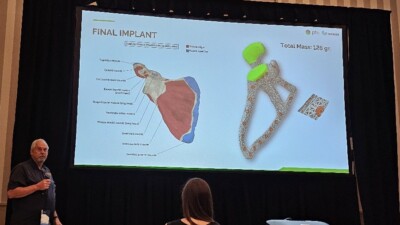

Sustainability initiatives aside, the primary reason biodegradable materials are so important in the context of AM concerns one industry in particular: medical devices. As a technology, 3D printing has flourished in medical device applications, with examples ranging from titanium implants to bioprinting organoid scaffolds. The ability to produce one-off, highly customized parts has given AM an edge in medical devices, but the next level for some of those devices is bioresorption.

Some devices, such as a tracheobronchial splint, have already entered clinical trials, but the first step in any case where the goal is for the patient’s body to absorb an implant, rather than merely tolerate it, is for the material of which that implant is made to be biodegradable.